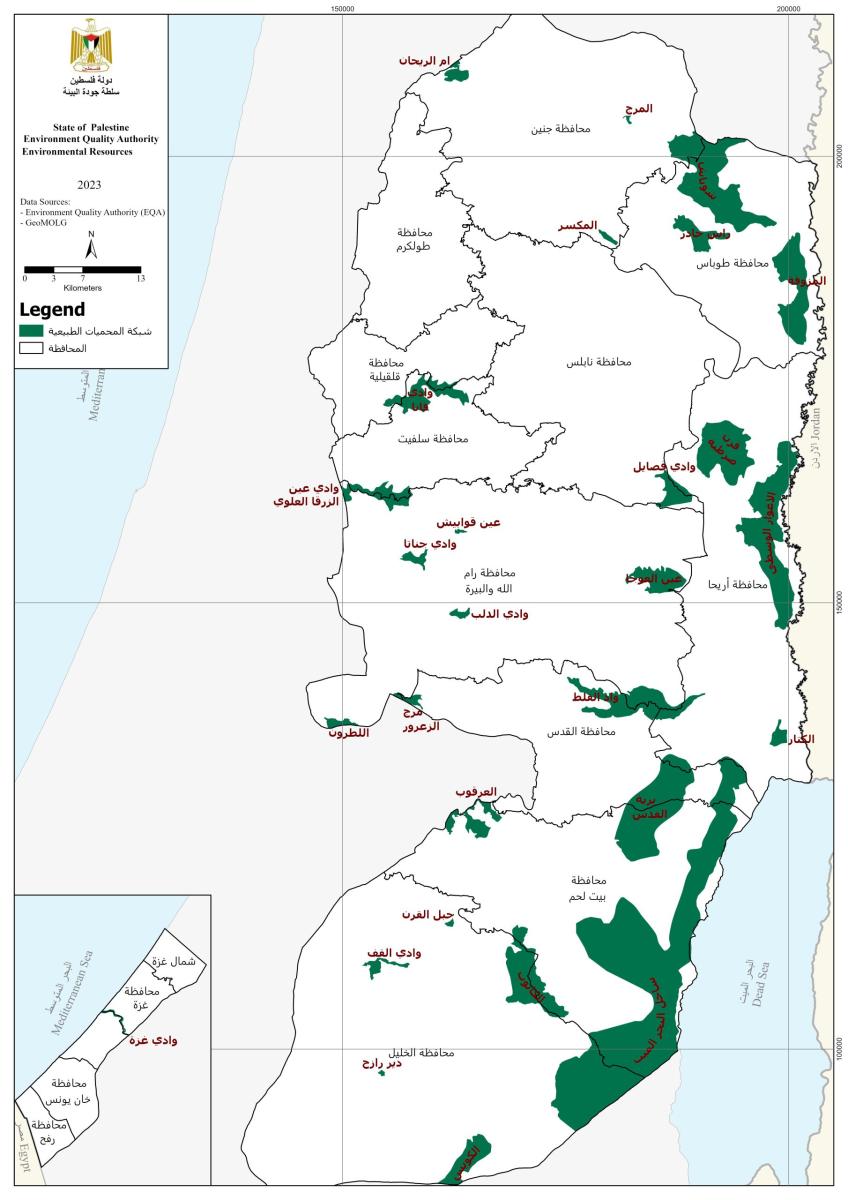

As noted in the sixth National Report, protected areas in the State of Palestine (SP) and areas of significant importance to them (like the Jordan Valley) are very limited in space. Only 9% of the land is protected in theory, and even less in practice and these are fragmented and little protected (for varius reasons including the Israeli occupation). The first step in addressing this issue is allowing the local people to have sovereignty over their land and natural resources, i.e. ending the Israeli occupation. The Protected Area Network (PAN) in Palestine has undergone a comprehensive evaluation and revision to ensure its effectiveness in conserving biodiversity. This re-evaluation was necessary as the previous PAN designated by the Israeli occupation authorities lacked clear rationale and included areas designated for non-biological reasons. The evaluation process led by IUCN, the EQA, Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Local government, and the Palestine Institute for Biodiversity and Sustainability involved analyzing the existing 50 areas of the PAN, as well as conducting Marxan analysis and incorporating new data based on IUCN criteria. The evaluation process led to eliminating, combining, and adjusting areas, resulting in a revised PAN consisting of 28 areas. This updated PAN represents all vegetation types and phytogeographical zones in Palestine, effectively protecting key ecoregions in the Mediterranean hotspot. The revision of the PAN has increased the total protected land mass from 9% to 9.98%. This expansion provides additional areas where biodiversity can thrive undisturbed, ensuring the long-term survival of species and ecosystems. The updated PAN was adopted at the highest level of government, signifying the importance and commitment to biodiversity conservation in Palestine. This achievement demonstrates the progress made by the state of Palestine in safeguarding its natural heritage.

Some areas like Wadi AlZarqa Al-Ulwi and Wadi Al-Quff (Qumsiyeh et al., 2016) could indeed be developed as biosphere reserves. UNESCO's Man and Biosphere (MAB) program had over a 50 year history of developing international cooperation related to human interaction with the biosphere. Over 700 biosphere areas in >120 countries are dedicated to conserving biodiversity, demonstrating sustainable development, and conducting research and education.

The SP benefited from many existing systems for Protected Area management. Dozens of books and resources and examples are available. For example, Natura 2000 is the largest coordinated network of protected areas in the world, stretching over 18% of the EU’s land area and more than 8% of its marine territory. Tools for monitoring of protected area management effectiveness can be found here. The METT template can be found on this page. The Protected Planet website here can be searched for particular protected areas including their WDPA ID.

A recent report on protected areas in SP, funded by a grant from the Belgian CeBios Measuring, Reporting & Verification (MRV) and expanded by IUCN/EQA/CEPF collective work on PANs in 2022, proposes:

- Ecosystem services and benefit sharing (Annex II of COP Decision 14/8) can be addressed by setting biosphere reserves that take into account local needs and challenges (Ganguly et al. 2003). There are guidelines from MAB . Wadi Al-Quff area is a very good candidate for this as it is a small area with a well-developed management plan

- Increasing sovereignty to give SP access to manage its nature reserves (currently many are considered area C) and utilization of international treaties and international laws to do this (Gillespie 2007; Sands and Peel 2012).

- More research and better planning: SP needs scientific data covering all areas of protected areas and potential protected areas by using the best available data collection methods on areas like geography, geology, hydrology, fauna, and flora. It is important in SP to build knowledge of species (profiles) and threats (see this example from Australia and one including recovery plans in the USA). “In each country, the appropriate national ministry or agency should recognize the interdependence of targets to expand protected area networks that are important for biodiversity conservation (e.g. Aichi Target 11 and GSPC Target 7) and actions to prevent the extinction of known threatened species through in situ conservation of viable populations backed up by ex situ measures where appropriate (Aichi Target 12 and GSPC Targets 4, 5, 7 and 8). Failure to do so will perpetuate the current failure to achieve these targets.” (Heywood, 2015). This also helps in prioritization since it is impossible to protect all threatened species. However, it is important to protect whole ecosystems rather than focus on individual species. An additional need is seen in order to perform more detailed studies on human impact on the environment caused by Palestinians or Israeli settlers (see Tal, 2002; Ginsberg, 2006; Abdallah and Swaileh, 2011; Al-Haq, 2015; Husein and Qumsiyeh, 2022).

- Controlling fires through planting indigenous trees and plants and reversing the planting of fire-prone European species through the colonial fund called Jewish National Fund (Keren Keyemet LeIsrael).

- Due to limited resources, it is critical to identify hotspots and key species to direct resources for conservation and to use buffer zones around protected areas with local buy-in.

- Creating and implementing a system of building capacity of developing leaders who are able to take on tasks in protected area management and strategies at a local, regional, and global scale. Towards that end, a bachelor degree program in Biodiversity and Sustainability has been established at Bethlehem University.

- Consider using the model of Plant Micro-Reserve (PMR) as used in Spain and Central and Eastern Europe when it is impossible to protect large areas (Kadis et al., 2014)

- A new vegetation map of Palestinian areas is needed. For history of earlier maps, see Zohary, 1947; Danin & Orshan, 1999, taking into account the shifting boundaries of the phytogeographical zones (Soto-Berelov et al., 2015). A good model for this in a neigbouring country in Taifour et al., (2022).

- Many of the protected areas sit on transitional zones, like El Kanub for instance, whose management needs special attention

- Restudy the area and produce more refined PAN periodically, starting with a revaluation in 2030.

- Reevaluate KBAs using global criteria (Langhammer et al., 2007). KBAs are “sites of global significance for biodiversity conservation. They are identified using globally standard criteria and thresholds, based on the needs of biodiversity requiring safeguards at the site scale. These criteria are based on the framework of vulnerability and irreplaceability widely used in systematic conservation planning.”

- Increase forested areas from 4% (Ministry of Agriculture) to 6% by 2050. Also, better management is needed of forests in protected areas (Dudley and Philips, 2006)

- A project to control invasive alien species in PAN is necessary (Foxcroft et al., 2013)

- IUCN Red Listing is important for area conservation, for informing spatial options (e.g. identifying important plant or bird areas) and informing temporal options, for example relating to previous destruction or threat analysis Red listing ecosystems can also be incorporated (Keith, 2015).

- There is a need to develop systems of permaculture and food sovereignty around PAN areas

- Uploaded data on PAN work on the CBD website

- Integrate PAN into spatial planning (Ervin et al., 2010).

The fragmented nature of the landscape in SP poses a challenge. Tabarelli et al. (2005) recommends dealing with such issues by: (1) incorporating protection measures as part of development projects; (2) protecting large areas and preventing the fragmentation of currently contiguous patches of forest; (3) managing forest edges when creating forest patches; (4) protecting gallery forests along waterways to connect isolated forest patches; (5) controlling the use of fire and the introduction of exotic plant species, and limiting the use of toxic chemicals in areas near forest patches; and (6) promoting reforestation and forest cover in critical areas of the landscape. Another major challenge for the EQA and relevant agencies in SP in implementing these steps is that there are few baseline studies which cover rich biodiversity areas, their location, distribution and what they contain. Maps of high concentrations of certain species show that the West Bank in particular has gaps, which is directly related to the lack of information or data collected in the West Bank (Levin and Shmida, 2007). Description of what we know so far is possible and then highlighting the gaps in the analysis and making recommendations for this area of work.

List of protected areas in the new PAN. The IUCN categories from I to VI are designated based on Dudley (2008) plus the intensive focus group and workshop meetings

|

Protected areas |

Arabic name |

Area (km2) |

Governorate/s |

IUCN category |

Other notes |

|

Dead Sea |

البحر الميت |

235.08 |

Jericho, Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Hebron |

IV |

The most important area with potential for designation under IUCN as Red Listed ecosystem |

|

Ein el Auja |

عين العوجا |

12.37 |

Ramallah and Al Bireh |

II |

Unchanged borders |

|

Jerusalem Wilderness area |

برية القدس |

52.84 |

Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Jericho |

Ib |

Newly designated PA |

|

Wadi el Qilt |

وادي القلط |

28.64 |

Jericho, Jerusalem, Ramallah and Al Bireh |

IV |

Very small adjustments in borders on the western side |

|

AlAghwar (Jordan Valley) |

الأغوار |

54.52 |

Jericho |

II |

Combining four previously adjacent areas |

|

Wadi Fasayil |

وادي فصايل |

8.38 |

Jericho, Nablus |

II |

Unchanged borders |

|

Al Kanub |

الكانوب |

29.02 |

Hebron |

IV |

Significant adjustments of borders |

|

Al Muzawqa |

المزوقة |

28.33 |

Tubas |

IV |

Border adjustments |

|

El Miksar |

المكسر |

1.22 |

Jenin |

IV |

Border adjustments |

|

Latrun |

اللطرون |

2.33 |

Ramallah and Al Bireh |

IV |

Newly designated PA |

|

Marj ez Zarur |

مرج الزعرور |

2.30 |

Jerusalem |

IV |

Unchanged borders |

|

Qarn Sartaba |

قرن سرطبة |

31.19 |

Jericho |

IV |

Border adjustments |

|

Umm er Rihan |

أم الريحان |

3.70 |

Jenin |

IV |

Border adjustments |

|

Wadi Ein ez Zarqa el Elwi |

وادي عين الزرقا العلوي |

10.53 |

Ramallah and Al Bireh, Salfit |

IV |

Border adjustments |

|

Wadi Jannata |

وادي جناتا |

2.80 |

Ramallah and Al Bireh |

II |

Border adjustments |

|

Wadi Qana |

وادي قانا |

15.30 |

Salfit, Qalqilya |

II |

Border adjustments |

|

Al Kuweiyis |

الكويس |

12.69 |

Hebron |

IV |

Border adjustments |

|

Ain Qawabish |

عين قوابيش |

0.452 |

Ramallah and Al Bireh |

V |

Border adjustments |

|

Deir Razih |

دير رازح |

0.352 |

Hebron |

V |

Border adjustments |

|

El Katar |

الكتار |

3.18 |

Jericho |

V |

Unchanged borders |

|

El Marj |

المرج |

0.41 |

Jenin |

V |

Significant adjustments of borders |

|

Jabal Al Qarn |

جبل القرن |

0.533 |

Hebron |

V |

Potential national eco-garden |

|

Ras Jadir |

راس جادر |

9.50 |

Tubas |

IV |

Significant adjustments of borders |

|

Shubash |

شوباش |

52.86 |

Tubas, Jenin |

V |

Potential biosphere reserve |

|

Al Arqoub |

العرقوب |

9.10 |

Bethlehem |

V |

Potential biosphere reserve |

|

Wadi Al Quff |

وادي القف |

3.44 |

Hebron |

V |

Potential biosphere reserve |

|

Wadi ed Dilb |

وادي الدلب |

1.56 |

Ramallah and Al Bireh |

VI |

Significant adjustments of borders |

|

Wadi Gaza |

وادي غزة |

2.84 |

Gaza |

VI |

Unchanged borders |

The 28 areas identified in the new PAN for the State of Palestine cover all vegetation classifications, all phytogeographical zones, key habitats, and the two ecoregions identified as part of the critical biodiversity hotspots in the Eastern Mediterranean region (the Conifer-Sclerophyllous broadleaf forests and the Jordan River basin habitats, Birdlife International, 2017). If managed well the PAN can protect the majority of known endangered and threatened species in Palestine. The PAN terrain includes:

- Western slopes (typical Mediterranean) include coastal elements near Qalqilya like Wadi Ein Al Zarqa Al Ulwi PA). Protected areas here are relatively small by necessity as they are located close to urban developments and settlement expansions.

- Eastern slopes: These are unique habitats with transitions from Mediterranean to Irano-Turanian to Saharo-Arabian elements.

- Jordan Valley area: This is a semi-arid area with an oasis and penetration of Sudanese-Ethiopian elements.

- Coastal (Wadi Gaza): With the potential to also include marine protected areas at a later date.

See the full report for the new Protected Areas Network in Palestine in the Link

See References in the Publications